Archive

Formulating a Response to the Satmars’ Secret Mass Gathering

Do you support this kind of behavior? If not, say so.

Earlier this month, we now know, the Satmar Jews of Williamsberg conspired to bring thousands of people together in reckless and flagrant violation of COVID safety procedures. A leaked photo of the event confirms a huge mass of people gathering indoors without masks or social distancing of any sort. And a Nov. 11 write-up in Der Blatt, a newspaper closely allied to the Satmars, confirms that organizers purposely concealed the event from “the ravenous press and government officials,” adding that “preparations were made secretly and discreetly.” So there is no doubt that (a) there was a dangerous mass gathering; and (b) organizers schemed to hide it from the public eye. These facts are not in dispute.

My question is what response this demands from Jewish leaders who do not support what the Satmars did.

I and many others have consistently chastised moderate religious leaders who refuse to denounce their more radical factions. An imam who doesn’t denounce a Hizballah suicide bombing, for instance, tacitly supports it, just as a minister who doesn’t denounce the bombing of an abortion clinic in Jesus’ name implicitly approves of it.

So it’s obvious to me that Jewish leaders must speak out, perhaps only briefly, or perhaps at length, if they object to the gathering. To stay silent after such a dangerous event is to endorse it.

To help such a response, here are a few facts:

- The recklessness of this event is unrelated to the recent Supreme Court case that, in effect, invalidated New York State’s capacity limitations on houses of worship, because recklessness does not necessarily involve breaking a specific law. There is no expert in the world who believes that the Satmar gathering was safe.

- This case is unrelated to the Establishment clause of the First Amendment that demands separation of church and state. No one doubts that local building codes apply to churches and mosques and synagogues, for instance, just as everyone agrees that even Kosher caterers must follow FDA safety guidelines. That’s because everyone agrees that government officials are permitted and even required to regulate matters of safety.

- As a matter of Jewish Law, it doesn’t matter if (as I believe) attending a wedding is a luxury, or if (as I think the Satmars may believe) attending a wedding is a commandment. Either way, the commandment of piku’ach nefesh — saving a life — takes precedence, in this case militating against a mass gathering of any sort for any purpose.

- The groom in this case was Rabbi Joel Teitelbaum. He is the grandson of Rabbi Aaron Teitelbaum, who is the Satmar head rabbi and the leader of the Satmar community. Rabbi Aaron Teitelbaum had both the authority and ability to limit attendees in furtherance of piku’ach nefesh. (I hope that he was simply too ignorant to know that COVID is dangerous. I fear that he didn’t care.)

- In October, the New York State health commissioner personally intervened to prevent a similar Satmar wedding planned for the same venue. That October wedding was scaled back, in contrast to this November one. Why, I wonder, could they scale back the first wedding but not this one?

Furthermore, the government’s greatest obligation is to protect its citizens, both reactively and proactively. So I believe that the strongest possible governmental response is called for here, and that the paltry $15,000 that New York City levied on Nov. 23 is insufficient. I also believe that Jewish leaders have an obligation to support the government as it pursues appropriate action against the Satmars.

My own response is this: In spite of the gulf that separates me from the Satmars religiously, politically, and ideologically, I consider them my brothers and sisters. This is why I am so pained by what they did. They hurt me and they hurt themselves. I want to be clear: They do not act in my name and I abhor what they have done. I hope people will not judge me or my community by their actions. And I am sad for the Satmars. They more than almost any other Jewish community should know how good America has been to them. (The Satmars are forbidden to live in Israel.) They are biting the fantastically generous hand that feeds them. To outsiders their ways appear primitive, misogynistic, and even deranged, yet they are afforded all the rights and privileges of citizenship in this country. Local hospitals will treat the Satmars who caught COVID at the wedding, just as local police will protect the cemeteries where they will be buried.

New York City parking laws were even changed to help the Jews celebrate Judaism. The City has welcomed two Jewish mayors. The State vigorously prosecutes acts of antisemitism. And the U.S. has empowered an unprecedented Jewish revival. In return, all the Satmars had to do was not hurt anyone. And, it seems, even that was too much to ask. How did it come to this?

Good Bye, Vassar Temple

Though I started working at Vassar Temple five years ago, I first heard about the place two years before that from my colleague and dear friend Rabbi Shoshana Hantman. “They’re a really nice group of people,” she was fond of saying about Vassar Temple.

With only a few exceptions, she was absolutely right.

Artistic gifts from students and teachers adorn my office door

And I say that having observed or consulted to hundreds of schools on five continents (soon to be six!). In fact, when I would tell my colleagues where I was working, the single most consistent response mirrored Rabbi Hantman’s remarks: “That’s a nice congregation,” frequently followed by a kind reference to Rabbi Arnold and Rabbi Golomb, and, most recently, Rabbi Berkowitz.

As I look back on five years, I certainly don’t want to minimize our technical accomplishments together. We built a thriving Hebrew school that draws members from neighboring congregations. We quadrupled the size of the post-bar/bat mitzvah Wednesday evening program. We grew the overall school by eight percent year over year when most religious schools are losing students.

Those feats, noteworthy in themselves, are also good for the financial heath of the congregation: good for the Jews and good for the bottom line, one might say. Or, as Rabbi Stuart Geller observes: the religious school is the financial engine that pulls the synagogue train.

So I don’t want to make light of bringing in new members or of increasing enrollment. But neither are these statistics the things that stand out most in my mind.

Rather, I remember non-tangible manifestations of a holy community.

For example, when our last Hebrew-school session of the year for grades 5-7 came to an end at 6:00pm on the Wednesday before Passover, the nearly 20 students in attendance refused to leave. Instead of bolting out of the school — as children so often do in other settings when class ends — they stayed behind, savoring a few final moments with each other and their Hebrew teachers. Surely this is what the Rabbis had in mind when they inserted the line into our morning liturgy, “make the words of your Torah sweet to us.”

When four Sunday-school teachers called in sick at the last minute last year, the remaining, healthy teachers jumped into action to run a constructive program together. One high school-aged teacher offered to teach a different class, improvising as she went. Another agreed to teach alone, though she had planned to work with a partner. And so on down the line. Though extreme, that day was hardly atypical, as teachers regularly volunteered to help each other out, never losing the smiles that came to symbolize our time together on Sunday mornings. What better way could there be to realize the Rabbis’ hope that we serve God together in joy?

Good-bye selfie

The list goes on: Sixth graders who eagerly anticipated their opportunity — though at least two years away — to teach in the school. Middle- and high-school students who insisted on starting each class with, “How was your week?” Grade-school students who were so proud of their work that they begged me to come into their classrooms for a closer look. Students who complained when I canceled class for snow that never arrived. Teachers who focused not just on what we were teaching but even more on who we were teaching.

In Pirkei Avot — “The Sayings of the Ancestors” from almost 2,000 years ago — Rabbi Shimon declares that the world is sustained by three things: Torah, service to God, and kindness. Later, still in the spirit of groups of three, he enumerates three crowns: the crown of monarchy, the crown of priesthood, and the crown of Torah. Then, having listed three, he adds a fourth, a crown that outweighs the other three: the crown of a good name.

More than a millennium later, Ovadiah ben Avraham of Bartenura wrote about this, suggesting that the crown of a good name refers specifically to a good reputation for doing good deeds.

Taken together, Ovadiah and Shimon tell us that being known for the right things is more important than royalty, more important than religious leadership, and even more important than Torah itself.

And this is what I will remember from my five years running the school at Vassar Temple: students, parents, teachers, leaders, and rabbis who in overwhelming majority are deservedly known for the way, through personal example, that they model the three things upon which the world stands: Torah, service to God, and great kindness.

Blessed is God, who crowns us with glory.

[An abridged version of this piece first appeared in the Vassar Temple June, 2016 bulletin.]

New Evidence on Who Wrote the Bible, and When

The world’s most popular piece of writing may have been written earlier than many people think. And it may have been more widely read.

In 2004, I suggested that the Israelites promoted widespread literacy early in the first millennium BCE, in part or perhaps primarily to help spread Scripture. My analysis, which appears in my NYU Press publication In the Beginning: A Short History of the Hebrew Language, is based largely on theoretical considerations like the ancient Israelites’ contributions to writing.

In 2007, the excellent scholar Karel van der Toorn published a competing theory in his Scribal Culture and the Making of the Hebrew Bible. He represents the more mainsteam view that literacy was limited to a very small scribal class. In my review of his work for the Jerusalem Post (apparently no longer available on line), I noted that:

Vexingly, then, we are left with two largely incompatible conclusions [van der Toorn’s and mine], each internally consistent and coherent, but unlikely both to be entirely correct. Puzzles such as these create exciting times for scholarship…

In an article just published in PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America) — available on line here for a fee and summarized here by the New York Times — an interdisciplinary team that includes mathematicians, archaeologists, and historians concludes that literacy was widespread in the Kingdom of Judah as early as 600BCE.

Their evidence comes from 16 inscriptions from Arad, an ancient military outpost south of Jerusalem. The style of the letters in the inscriptions points to at least six different ancient literate writers. The content of the inscriptions suggests that even low-ranking officials wrote things for themselves.

In fact, the authors identify five rungs of hierarchy represented by the inscriptions, starting with the king of Judah and running through a high-ranking commander, a local commander in Arad, and a quartermaster in Arad named Eliashib down to Eliashib’s subordinate. Even that subordinate, apparently, was literate.

The authors conclude that literacy in Judah was widespread far earlier than scholars like van der Toorn have thought.

Combined with my largely theoretical evidence in In the Beginning, we now have even more reason to believe that parts of the written text of the Bible date to the early first millennium BCE.

Additionally, it seems that widespread literacy was an integral part of the ancient Judaean agenda, alongside other more widely noted goals such as monotheism.

Why Mississippi’s Religious Liberties Law Is More Nuanced Than You Think

Do you think that a wedding florist should be allowed to deny service to a gay couple just because they’re gay?

Do you think that a wedding florist should be allowed to deny service to a gay couple just because they’re gay?

Do you think that a Jewish photographer should be allowed to refuse photography services to a Neo-Nazi group just because of the nature of that group?

Do you think that a store — on religious grounds — should be allowed to refuse insurance coverage for birth control?

Do you think that an advertising agency — on contrary religious grounds — should be allowed to refuse to help that store’s owners explain their position?

If you have different answers for these four questions, then you appreciate the complexity of Mississippi’s controversial “Protecting Freedom of Conscience from Government Discrimination Act” (HB 1523), which was just signed into law; of Georgia’s similar “Free Exercise Protection Act” (HB 757), which that state’s governor vetoed; and of similar legislation.

If you have different answers for these four questions, then you appreciate the complexity of Mississippi’s controversial “Protecting Freedom of Conscience from Government Discrimination Act” (HB 1523), which was just signed into law; of Georgia’s similar “Free Exercise Protection Act” (HB 757), which that state’s governor vetoed; and of similar legislation.

Mississippi’s law claims to protect people, and groups of people, who act based on a “sincerely held” belief or “moral conviction” in any of three hotly debated tenets:

- Marriage is only between one man and one woman.

- Sex should be confined to such a one-man-one-woman marriage.

- People have only one gender (“sex”), the biological one with which they were born.

Opponents to the law say it legalizes discrimination against, for example, gay couples.

Proponents counter that it protects religious freedoms.

In my opinion, both claims are right (though that doesn’t mean that I think both sides have equal merit). The Mississippi law generates such vehemence precisely because it pits one cherished American value against another.

In this country we believe in equality before the law. We have already established, for instance, that it’s illegal to set out to hire men instead of equally qualified women, no matter how much an employer may prefer working with men.

In this country we also believe in freedom of religion. We have already established, for instance, that the Church can bar women from certain positions of leadership, no matter how qualified they might otherwise be.

Or to look at it differently, the opponents to Mississippi’s law say that, in this case, equality trumps religious freedom. Proponents say that these religious freedoms trump equality.

And here, I think, is the real issue: when these two supreme values collide, which one do we, as a society, choose? And why?

Unfortunately, the public conversation plays out differently.

Proponents double down, defending their religious position, for instance, that marriage is, was, and always shall be between one man and one women. (I think they’re wrong, but that isn’t the point.) They ignore the fact that similar religious arguments were advanced in the 19th century to defend slavery. And they ignore the fact that even Christian-owned stores are not allowed to discriminate against women, even though the Church is.

Opponents also double down, defending their position, for instance, that a marriage between two men is just as valid as a marriage between a man and a women. They ignore the fact that they might experience supreme discomfort if they had to work in support of the KKK. (The KKK probably takes offense at my position, but that isn’t the point.) And they ignore the fact that laws already permit religious gender-based discrimination.

So I have a challenge:

If you defend this law, why do you think that these particular religious beliefs are more important than equality? That is, how is an anti-gay-marriage stance different than, say, 19th-century pro-slavery religious beliefs or, more generally, other gender-based religious beliefs?

If you oppose this law, why do you think that these particular religious beliefs should be squashed? That is, how is forcing people to support gay marriage different than, say, forcing people to work on their sabbath, or forcing people to support other things they don’t like, such as perhaps, the KKK?

And in the meantime, as we continue to discuss this law, perhaps we can at least tread softly out of respect for people who disagree with us.

“The Bible Doesn’t Say That” Goes On-Sale Today!

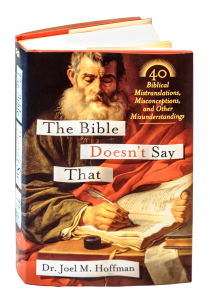

My latest book — The Bible Doesn’t Say That: 40 Biblical Mistranslations, Misconceptions, and Other Misunderstandings — goes on sale today!

My latest book — The Bible Doesn’t Say That: 40 Biblical Mistranslations, Misconceptions, and Other Misunderstandings — goes on sale today!

Here’s the cover copy:

The Bible Doesn’t Say That explores what the Bible meant before it was misinterpreted over the past 2,000 years.

Acclaimed translator and biblical scholar Dr. Joel M. Hoffman walks the reader through dozens of mistranslations, misconceptions, and other misunderstandings about the Bible. In forty short, straightforward chapters, he covers morality, life-style, theology, and biblical imagery, including:

• The Bible doesn’t call homosexuality a sin, and it doesn’t advocate for the one-man-one-woman model of the family that has been dubbed “biblical.”

• The Bible’s famous “beat their swords into plowshares” is matched by the militaristic, “beat your plowshares into swords.”

• The often-cited New Testament quotation “God so loved the world” is a mistranslation, as are the titles “Son of Man” and “Son of God.”

• The Ten Commandments don’t prohibit killing or coveting.

What does the Bible say about violence? About the Rapture? About keeping kosher? About marriage and divorce? Hoffman provides answers to all of these and more, succinctly explaining how so many pivotal biblical answers came to be misunderstood.

The table of contents is on-line here, and you can learn more about the book here. Publishers Weekly has a pre-review here.

I’m excited about this latest work, and look forward to discussing it here.

So What, Exactly, is Tu Bishvat?

The evening of January 24th marks the start of Tu Bishvat this year. The name means the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Shevat, and it refers to the so-called “new year of the trees.”

The evening of January 24th marks the start of Tu Bishvat this year. The name means the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Shevat, and it refers to the so-called “new year of the trees.”

Why do trees need a new year?

For an answer we turn to the Talmud — that great compilation of Jewish laws and lore from the middle of the first millennium CE. The section called “Rosh Hashana” (“New Year”) starts with the intriguing claim that “there are four new-year days.” And it turns out they fall in the months of Nissan, Elul, Tishri, and Shevat.

The new year with which we are now most familiar — Rosh Hashana — falls in Tishri, which, as it happens, is the seventh month of the year. Certainly the year ought to begin with the first month, so we know we have some digging to do.

The first month is Nissan. Passover falls on the 15th day of this month, and the first day is what the Talmud calls the new year for kings and festivals.

Elul is the sixth month, usually overlapping August and September in our calendar. The first of Elul is the new year for the cattle-tithe.

After Elul comes Tishri, the first day of which is New Year’s Day. As we just just saw, this puts the Jewish new year in the middle of the Jewish year.

And then we get to Shevat, the 11th of the 12 months in the Jewish year. The Talmud advises that some people thought that the 1st day of Shevat was the new year for trees, but the prevailing opinion relegated that status to the 15th day of the month.

Fine. So we have, working our way through the year, the new year for kings (in the 1st month, a couple of weeks before Passover), the new year for cattle-tithes (in the 6th month), New Year’s Day (on the first day of the 7th month), and then the new year for trees in the 11th month.

The Talmud explains why kings need their own new year, starting with a cryptic answer: “on account of documents.” It turns out that documents such as mortgages were dated according to the year of a king’s reign — as in, “during the second year of the reign of King So-and-So.” The question is when that second year commences. Is it on the anniversary of his ascension to the throne? No. It’s on the new year for kings. So along with each first day of Nissan there begins a new year for reckoning time according to the reign of kings.

What about the cattle-tithe new year? It used to be that people would pay yearly taxes of a sort based on how many animals they had. To implement this system, an arbitrary cut-off date for counting the animals was required. For instance, you might have 15 heads of cattle on one date, and 20 an another. At what point would you pay for the additional animals? The answer is that the 1st of Elul was the cut-off date. You paid taxes each year on however many animals you owned on Elul 1. (The IRS uses the same principle in calculating income tax. Tax on money earned up to December 31 of one year is due by April 15 of the next year.)

Similar reasoning applies to the new year for trees. Taxes were paid on fruit trees. A tree whose fruit was fully formed before Tu Bishvat of a given year was taxed in its entirety during that year; if the fruit formed thereafter, it was taxed in the next year.

Of course, we no longer reckon our years by kings and no longer pay tithes on the animals or on the fruit trees that we own. (And in any event, my animals number zero each year.) So why should we care?

Beyond the interesting if now-irrelevant details, and the spotlight on our history, we find meaningful customs that have come to accompany the different new years. On Tu Bishvat, for instance, we now pause to honor trees and nature in general.

In addition, we learn that our lives have more than one yearly cycle. Natural patterns commence around Passover, with the onset of spring, just as things like school calendars begin in the fall, and our official American calendar resets in the middle in winter. And thanks to a long sequence of interpretation, January 24 marks yet another fresh start.

Happy new year.

Mi Y’malel Fantasy

A Fantasy based on the traditional melody for Mi Y’malel. Enjoy!

Let’s Get a Few Things Straight about Hanukkah

As with so many things, the problem started with Alexander the Great, and, in particular, with what he didn’t do.

Just over 2,300 years ago, Alexander III “The Great” of Macedonia was a young man of 32 who had conquered the known world in just a decade — a feat marked to this day by the names of cities like Alexandria, Egypt, and, 2,000 miles further east, Kandahar, Afghanistan. Alexander’s first wife was seven month’s pregnant, and — in both a literal and figurative marriage of east and west — he had just taken the daughter of the defeated Persian ruler Darius III as a second wife. How could Alexander have known that he wouldn’t live long enough to be a father?

Demonstrating understandable but ill-fated short-sightedness, Alexander had therefore not created a plan of succession, so his death brought huge instability, with various generals and other power brokers vying for control.

Four points define the geography of the ancient world: Greece in the west; Persia (Iran) in the east; Egypt in the south; and Syria, where the journey north from Egypt intersects the east-west trail from Greece to Persia. So power centers were established in those four places. (It is not coincidence that, more than 2,000 years later, Iran, Egypt, Syria, and Greece still dominate the news.)

Jerusalem had the misfortune of lying just off the path from Syria to Egypt, so every time the new Syrian dynasty and the new Egyptian dynasty fought, Jerusalem was part of the battleground. For a while Egypt had the upper hand, and Jerusalem was part of Egypt. Then around 200 BCE, the Syrian ruler Antiochus III “The Great” won Jerusalem and turned it into a Syrian province.

That wouldn’t have been so bad but for the fact that Antiochus III had a son, Antiochus IV. The details are complex — and involve familiar figures like Hannibal — but the upshot is that Antiochus IV was taken into Roman captivity, only to be freed later for another Syrian ruler’s son.

While Antiochus III’s nickname was “The Great,” Antiochus IV was dubbed “The Insane.” And this was not good news at all.

Antiochus IV tried to quash Jewish practice in Jerusalem.

This is the Antiochus against whom the famous Maccabees took up arms.

The Maccabees — led in large part by Judah Maccabee — prevailed. This is the victory we celebrate at Hanukkah.

Because Antiochus IV was from Syria, some people say that the Maccabees fought the Syrians. And because Antiochus IV was part of the Greek dynasty that took over Syria after Alexander the Great’s death, other people say that the Maccabees fought the Greeks. This is why different versions of the Hanukkah story variously refer either to the Syrians or to the Greeks.

So Hanukkah originally commemorated the violent overthrow of violent and unstable Syrian Greek rulers.

Unfortunately, the Maccabees, while able fighters, were less capable rulers. For instance, Simon — one of the five Maccabee brothers — served as high priest of Jerusalem. Then one of his sons, John Hyrcanus I, took over. The reason that Hyrcanus was next, rather than one of Simon’s other two sons, is that Simon’s son-in-law had murdered them, along with Simon himself. And astonishingly, those events were peaceful compared to what would follow.

Later — perhaps because of the dubious optics of a holiday that commemorated overthrowing the government — Hanukkah was recast in terms of the familiar light and darkness, oil and miracles.

But I think those four elements were actually there from the outset. We see from the full story what we already knew: Life is complex and messy. We have periods of light and periods of darkness. The path to the light is often a mundane one that’s based far less in lofty theology and far more in our day-to-day existence.

Oh yes. And, if we look carefully, we find that life is marked by miracles.

Happy Hanukkah.