Archive

Devout or Deranged?

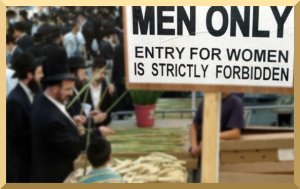

The AP recently reported that some ultra-Orthodox men, “in an effort to maintain their strictly devout lifestyle,” are now buying sight-blurring eye-glasses in order to avoid seeing women (“Ultra-Orthodox Jewish men offered blurry glasses look to keep Israeli women out of sight“).

The AP recently reported that some ultra-Orthodox men, “in an effort to maintain their strictly devout lifestyle,” are now buying sight-blurring eye-glasses in order to avoid seeing women (“Ultra-Orthodox Jewish men offered blurry glasses look to keep Israeli women out of sight“).

Is this really “devout”? Or is it deranged?

I want to be clear: I support freedom of religion. And as fanaticism goes, blurry eye-glasses seem pretty benign, especially in the context of the increasingly common connection between religious zealotry and explosives. But why do we call this behavior “devout”?

If the Oxford English Dictionary is to be trusted, “devout” is anything that has to do with devotion to the divine. But for me, and, I suspect, most other English speakers, “devout” implies that in addition to being religious, the behavior is (1) unusual, (2) authentic, and (3) desirable.

If the Oxford English Dictionary is to be trusted, “devout” is anything that has to do with devotion to the divine. But for me, and, I suspect, most other English speakers, “devout” implies that in addition to being religious, the behavior is (1) unusual, (2) authentic, and (3) desirable.

The first quality is why the AP (again, following common usage) applies “devout” to the ultra-Orthodox, but not, say, to me in my role of Religious-School director, or to my father is his role of rabbi. Both of us look like most other Americans, while the ultra-Orthodox attire is unusual. Similarly, giving charity and helping the downtrodden is a way many people express devotion to God, but precisely because so many people do them, those practices seldom earn the adjective “devout.”

It’s the second and third qualities that concern me. Both the ultra-Orthodox men (when they oppress women) and the Taliban (when they blow up infidels) are doing what they think is God’s will. When we call the first group “devout” and the second “fanatical,” we are tacitly giving approval to what the ultra-Orthodox do. It’s as though we’re making the case that misogyny is like kindness: laudable, even if we aren’t all always up to the task.

I think that a different division is called for. We should be clear that the blurry glasses are part of a cult of fanaticism, along with segregated buses and other modern inventions of a group of people calling themselves the guardians of tradition. The Taliban are likewise fanatics. And I suppose there are those for whom my own religious practice of lighting plain white candles Friday evening before it’s even dark could come under the category of fanatical. Fanaticism comes in many varieties, and either it’s all devout or none of it is.

It seems to me that the important distinction here is between benign and destructive. When I light Sabbath candles, I’m not hurting myself or anyone else. The same cannot be said for segregated buses or suicide bombers.

I’m not entirely sure where the blurry glasses fall, but either way, I think the AP does everyone a disservice when it excuses some otherwise detestable behavior by calling it “devout.”

Two Monologues And No Dialogue: How (Not) To Talk About Religion and Social Issues

The past few days have highlighted for me once again the degree to which our religious nation is divided.

The past few days have highlighted for me once again the degree to which our religious nation is divided.

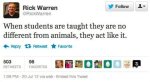

The first example comes from the hugely popular megachurch pastor Rick Warren and his recent reaction when a man slaughtered moviegoers in Aurora, CO. Pastor Warren blamed the violence on those who teach evolution. “When students are taught they are no different from animals, they act like it,” he wrote on his Twitter and Facebook accounts. (He has since deleted his tweet, but not before on-line media such as The Examiner wrote about it.)

The first example comes from the hugely popular megachurch pastor Rick Warren and his recent reaction when a man slaughtered moviegoers in Aurora, CO. Pastor Warren blamed the violence on those who teach evolution. “When students are taught they are no different from animals, they act like it,” he wrote on his Twitter and Facebook accounts. (He has since deleted his tweet, but not before on-line media such as The Examiner wrote about it.)

The second example comes from The Gospel Coalition’s collection of blogs, which featured a post by author and pastor Jared Wilson. In it, Pastor Wilson explains that God’s natural order of things is for men to dominate women, and that rape results from men and women who try to fight that God-ordained hierarchy. (Like Pastor Warren, Pastor Wilson removed the blog post, under protest. Excerpts and an analysis can be found here: “Complementarians and Martial [sic] Sex: The Jared Wilson / Gospel Coalition Saga.”)

The same Gospel Coalition is promoting an anti-homosexual marriage blog post: Gay Is Not the New Black, written by Pastor Voddie Baucham.

The same Gospel Coalition is promoting an anti-homosexual marriage blog post: Gay Is Not the New Black, written by Pastor Voddie Baucham.

Most of the reactions to these kinds of claims come in one of two varieties: (1) How could anyone possibly agree? or (2) how could anyone possibly disagree?

The naysayers cite their evidence: Pastor Warren has misunderstood the allegorical nature of Genesis, and misunderstood the natural world in that animals don’t tend to slaughter their own kind. Pastor Wilson has ignored passages such as 1 Corinthians 7:3-5 that put men and women on a par in the marriage bed. Pastor Baucham has taken 1 Corinthians 6 out of context while ignoring other relevant passages of Scripture. And so forth.

Then the claimants respond with their own evidence: Morality comes from religion, Colossians 3:18 subordinates women to men, and Leviticus forbids homosexuality.

As a Bible scholar, it’s abundantly obvious to me that both sides find ample support in Scripture. The Bible doesn’t take a clear stance on evolution, why people commit violence, or what marriage looks like — not beyond what we all agree on, at least.

But I don’t think that these are debates about evidence, science, or religion. In fact, I don’t think they are debates at all. They are, rather, collections of diatribes — monologues, as it were, instead of dialogues. And that’s because we tend to focus on our self-selected evidence instead of our motivations.

For example, if Pastors Warren, Wilson, and Baucham discovered that they were wrong about the intent of the Bible (as I believe they often are), would they change their minds? If a new manuscript surfaced, or a better understanding of the text presented itself, would they care? My suspicion is they would not.

Like slavery in its day and usury before that, these issues don’t start with the Bible. They start with how we feel.

So if we’re going to have a real conversation, I think it has to be about our motives, not the texts we choose to support them.

A Tale of Customer Service and Customer Disservice

A curious thing happened to me on the way home from a conference in Detroit: Delta Airlines gave me a hotel voucher for the Westin in the airport, and the Westin refused to honor it.

A curious thing happened to me on the way home from a conference in Detroit: Delta Airlines gave me a hotel voucher for the Westin in the airport, and the Westin refused to honor it.

What’s really interesting is the difference between the follow-up response from Delta and from Westin and its parent company, Starwood Hotels. Delta tried to help and Starwood tried to cast blame.

The background is this: Weather was creating havoc across the eastern seaboard with practically no flights landing anywhere from Washington to New York, so my 5:30pm flight from Detroit to LaGuardia was delayed. By 6:30pm, the 3:30 to New York hadn’t left yet, the 5:30 (my flight) was tentatively scheduled for 7:45, and the 8:15 flight had an estimated departure time of 10:30. It was a mess.

I explained to Delta that I had been at a five-day conference and I was exhausted. If I landed in New York at 9:30, I thought I’d still be able to drive home safely. But if I landed at, say, 11:00, or (as was predicted for the 8:15-revised-to-10:30 flight) around midnight, I’d be too tired to drive. Could they help?

It was a gray area. On the one hand, the delays were weather related, and the airlines don’t usually take any responsibility for anything that might even rhyme with weather. On the other hand, I expressed my concern that Delta couldn’t give me solid information, and I had to make a decision. A supervisor agreed to put me up in a hotel, and then a desk agent started phoning around to find out where there was space. Fifteen minutes later, she told me that the Westin, actually in the airport, had a room for me. (Delta also gave me a $6 voucher for dinner, which is fine if all you want is a chocolate-chip cookie and a bottle of water to wash it down — but that’s for another day.)

Ten minutes later I handed the hotel voucher to an immaculately-dressed and hyper-polite desk agent at the Westin. After scrutinizing the document, he seemed concerned, though he didn’t tell me why. “Let me make a phone call,” he said and disappeared into the office behind the check-in desk. I thought he was new and didn’t know what a voucher was, or perhaps didn’t know how to process it. I was sure that some better-trained employee would set him straight.

But when he came back he told me simply, “I won’t accept this.”

“May I please speak to a manager?” I asked.

“I am the manager.”

Oh.

It took a few minutes for me to learn that he didn’t have any rooms for voucher customers. That didn’t seem fair, and I told him so.

The manager agreed to make a few more phone calls. Some twenty minutes later I learned that, in fact, he didn’t have any rooms at all. His phone calls had been to try and find out who had made the mistake.

“I don’t care who’s at fault,” I told him — though my suspicion was and still is that the Westin gave my room to a VIP Westin customer even though they’d already promised it to Delta. “All I need is a hotel room, here or somewhere else. Can you help me? Do you have provisions for this sort of thing?”

He wouldn’t help me.

At this point I was balancing a few competing factors: I needed a hotel room. I also had to pick up my checked bag from baggage claim, and I was worried that if I waited too long they’d put it somewhere where it could be retrieved only after a lengthy wait in line. My cell phone didn’t have reception in the Westin lobby, so I couldn’t make any arrangements for myself from there. But the manager had left a voice message (or so he said) at Delta and they were on their way to help.

I decided to leave my carry-on at the Westin, run to baggage claim, get my bag, and run back as fast as possible, hoping not to miss Delta.

As it happened, I wasn’t late to baggage claim but early, a fact I learned when I didn’t see my bag and had to wait in (a mercifully short) line after all. There a Delta agent helped me track down my bag. I mentioned something like “at least one thing is going right,” and when she asked what I meant, I told her about the hotel. “Well let’s find you another hotel,” she said. And she did.

I went back to the Westin, got my carry-on, and took a shuttle to the Best Western, where a room key was waiting for me. Having just joined Twitter a little while ago, I tweeted a question to @DeltaAssist, copying @StarwoodBuzz and @Delta.

And this is where things really get interesting. Apparently from my tweet it wasn’t clear that I had found a replacement hotel.

Delta replied immediately offering to help.

Starwood also replied, publicly blaming Delta: “This seems to be an error on Delta’s end.”

My point here is not who made the initial mistake. I really don’t care. I have the manager’s name from the Westin, for example, but I’m not publishing it.

Rather, I think this is an example of two kinds of cultures: helping and blaming.

I’ve written before about the value of customer service (“For $12.17 you can have the best school in the country“), in the context of TD Bank helping me with a mistake that was my own fault.

It seems to me that helping a person no matter who is at fault, and whether or not the person is a current customer, is both kind and good business sense. Yet remarkably few businesses will spend money/time/energy/resources to help a person when they don’t think there’s any immediate financial gain in doing so.

I spend most of my professional life with faith-based not-for-profits, and, perhaps surprisingly, it’s been my experience that they tend not to do any better. They’ll often help a person only when it’s specifically part of their mission — because the person is a member, say, or a grant recipient.

What are the policies and culture where you work? Do you help or do you blame?

Dawkins, Religion, Morality, and the Importance of Being Informed

In a video interview on Al Jazeera English, the well-known Professor Richard Dawkins is asked why murder is wrong if life isn’t sacred (about 29:45 into the video). “Where do we get the notion of morality,” a caller asks, “from physics or from God?”

It’s an excellent question.

Unfortunately, Dr. Dawkins — usually known for using evidence to support his positions — here essentially reprimands the caller for asking a stupid question: “I cannot believe you’re suggesting” that there could be morality only with God. “Do you seriously think,” he continues mockingly, that people didn’t know that killing was wrong until Moses came down Mt. Sinai with the Ten Commandments and told the people “thou shalt not kill.”

Unfortunately, Dr. Dawkins — usually known for using evidence to support his positions — here essentially reprimands the caller for asking a stupid question: “I cannot believe you’re suggesting” that there could be morality only with God. “Do you seriously think,” he continues mockingly, that people didn’t know that killing was wrong until Moses came down Mt. Sinai with the Ten Commandments and told the people “thou shalt not kill.”

To me (as I said at the very start of my TEDx presentation), this is like saying that of course we don’t need farmers any more because we can get food from supermarkets. I might equally ask Dr. Dawkins, “do you seriously believe that we need people to grow fruits and vegetables when they’re available at any supermarket?”

More specifically, Dr. Dawkins’ response is troubling for three reasons:

- I think he’s misunderstood the role of religion.

- I know he’s misquoted the Bible.

- I think he’s wrong.

The Role of Religion

Dr. Dawkins seems to be missing the essential point. He says that everyone knows murder is wrong, that there are certain evolutionary reasons to come to abhor murder, that it’s better to live in a society where people don’t kill for no reason, and so forth. But even if all of that is true, it’s religion that encodes this important information, and it’s religion that brings the message to people who are trying to decide how to live their lives.

In other words, even if Dr. Dawkins is right that God has nothing to do with morality because some things are immoral simply because they are immoral, it’s still religion that occupies itself with pushing people toward doing what’s right.

The Importance of Being Informed

Ironically, just before the question about morality, Dr. Dawkins stresses that “people who don’t know what they’re talking about should keep quiet,” yet then minutes later he misquotes the Bible to make his point about religion.

It’s well know that the translation “thou shalt not kill” is inaccurate. (I go through all of the evidence in chapter 7 of my And God Said: How Translations Conceal the Bible’s Original Meaning. The short version is that the commandment only applies to illegal killing, and the point is that laws about killing, unlike some other laws, are both matters of law and of morality.) In other circumstances, Dr. Dawkins might be forgiven for relying on a mistranslation, but here he’s trying to speak to the very nature of religion and he’s asserting that he knows what he’s talking about.

The point of the Ten Commandments is that some things are not only illegal but also immoral, and illegal killing is one of those things. (Again, I go into more detail in my TEDx presentation, starting around 15:20 into the video.) So it’s important to distinguish between “kill” and “kill illegally” (“murder” is pretty close, though a little too narrow, because some killing is illegal but not murder).

More generally, Dr. Dawkins seems not to understand the role of religion that he is attacking. He seems to think that, according to the Ten Commandments and religions based on them, the only reason not to murder is that God might catch you and punish you. Some people believe this. But another religion-based approach is that these things are wrong because God doesn’t want us to do them, even if God doesn’t actually punish us.

This is no different than making murder illegal — a step that probably makes sense even though most people wouldn’t murder even if it were legal, and some murderers don’t get caught.

Morality

Perhaps most importantly, I think Dr. Dawkins is wrong.

I imagine a thought experiment. You’re a sharpshooter and you’re flying over an island in international waters. As it happens, two people are living on the island. No one (except, now, you) knows they’re there. They have no living relatives. And they’re too old to have children. Because you enjoy your craft you take aim and shoot them both dead. Have you done anything wrong?

My answer is yes, because it displeases God.

My question is whether Dr. Dawkins thinks it’s wrong, and, if so, why? After all, no one suffers. No one is around to mourn their death, and (because Dr. Dawkins admits no afterlife of any sort) they themselves don’t care that they’re dead. Because the island is in international waters, it’s not even clear that any laws have been broken. In fact, the world may be better off, because you’ve had a fun day, there’s a tiny bit more oxygen left for the rest of us, and you’ve improved your skills, which you can now put to good use.

I suppose Dr. Dawkins would mock me, as he did the caller, for asking, but I’ve been asking this question for 20 years, and I have yet to hear a satisfactory answer other than, “it’s wrong because of some external determination.”

I call that God.

An Open Letter to CNN’s Piers Morgan

[Update: An expanded version of this letter, with additional information about how I read the Bible regarding homosexuality, is available on the Huffington Post. (June 5, 2012)]

Dear Mr. Morgan:

I believe you have been promoting bigotry and helping to perpetrate a fraud.

During both of your interviews with Pastor Joel Osteen on your CNN broadcast, you let the religious leader tell your audience that Scripture calls homosexuality a sin. But you didn’t ask him where the Bible says that.

During both of your interviews with Pastor Joel Osteen on your CNN broadcast, you let the religious leader tell your audience that Scripture calls homosexuality a sin. But you didn’t ask him where the Bible says that.

It’s both an important point and an easy one to settle. You could have asked Pastor Osteen for the chapter and verse that he thinks calls homosexuality a sin. What you would have found is that he couldn’t provide it, because Pastor Osteen was expressing his personal opinion, not quoting the Bible. The Bible doesn’t say that homosexuality is a sin.

It seems to me that Pastor Osteen, as a religious leader, has a right to believe what he wants and to encourage others to follow. So if he doesn’t accept homosexuality, it’s his prerogative to spread his anti-homosexuality message. But I think it’s dishonest when he pretends that his opinions are those of the Bible.

Similarly, if you don’t like homosexuality, it’s your right to say so on air. But I think it’s irresponsible of you to let a guest tell your audience that something is in the Bible without even asking where.

This glaring omission is all the more surprising in light of your claim to be “challenging.” Why didn’t you challenge Pastor Osteen on this basic factual issue?

I look forward to your response.

Sincerely,

Joel M. Hoffman, PhD

+1.718.834.1080

[email protected]

http://www.Lashon.net

| Copies: | Meghan McPartland, [email protected] |

| Jonathan Wald, [email protected] | |

The Apostle Paul did not Believe in the Historical Adam

A debate has been raging about whether Adam was an historical figure. I think it’s important, because it represents a more general debate about how to live a modern religious life. I also think it highlights a fundamental misunderstanding.

The historical Adam is apparently important for fundamental Christian theological reasons, which is why Dr. Albert Mohler, Jr., president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, wrote that, “The denial of an historical Adam and Eve as the first parents of all humanity … produces a false grasp of the Gospel” and told NPR that “without [an historical] Adam, the work of Christ makes no sense…”

The historical Adam is apparently important for fundamental Christian theological reasons, which is why Dr. Albert Mohler, Jr., president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, wrote that, “The denial of an historical Adam and Eve as the first parents of all humanity … produces a false grasp of the Gospel” and told NPR that “without [an historical] Adam, the work of Christ makes no sense…”

His basic point, shared by many others, is that, “the Apostle Paul … clearly understood Adam to be a fully historical human.”

It may surprise some that I don’t agree at all. I don’t think that Paul believed in an historical Adam.

I think that the whole notion of “historical” is a modern one, created by modern science, and that it’s this entirely modern approach that pits history against myth. Paul didn’t believe in an historical Adam or a non-historical Adam. He just believed in Adam. It’s only as modern readers that we divide things — for ourselves — into historical and non-historical.

Even ancient historians like Herodotus (5th century BC) and Josephus (1st century AD) freely mixed what we would now call history with literature. As part of their histories, they included verbatim conversations that they had no way of knowing. Similarly, they mixed history with myth, as when Herodotus writes about the phoenix in the same terms as the crocodile or when Josephus, whose life overlapped with Paul’s, describes a cow that gave birth to a lamb during his own lifetime.

So while I understand the modern inclination to ask whether or not the Adam that Paul believed in was historical, I think it’s an anachronistic question. And more than any answer to it, it’s the question itself that parts with Scripture.

[Update: John Farrell has a review on Forbes.com of Peter Enns’ new book, Evolution of Adam: What the Bible Does and Doesn’t Say About Human Origins, including a discussion of some issues surrounding the historical Adam. Also, Dr. Enns just posted a 40-minute lecture in which he talks about the material in his book. (5/14/2012)]

[Update 2: Along similar lines, my father, Rabbi Larry Hoffman, has a piece that I think everyone should read: “Even if every bit of the Bible were literally true, it would still be fiction because…” Read the rest. (5/31/2012)]

[Update 3: Bible Gateway has a series of four videos with four views about the historical Adam: New Videos: Did a Historical Adam Really Exist? (1/22/2014)]

How Maximizing Profits is Making Life Worse for Everyone

It is well known that people are generally sensitive only to big relative changes, and tend not to care about, or even notice, small ones. This is why three shots of vodka is much more than one, but if you add two shots of milk to a gallon of milk, you still have about a gallon. They’re both a 3-ounce addition, but the vodka increased 200%, the milk only about 2.5%, and we notice the percentage, not the absolute amount. Similarly, a fifteen minute car ride feels longer than a five minute one, but seven hours and 15 minutes on a flight doesn’t seem different than only seven hours and five minutes. A child who grows from four feet to five has shot up, while a mountain in the Rockies that goes from 8,200 feet to 8,300 looks the same.

This can be a problem when small changes yield big profits. If, for example, you could earn a million dollars by making your house only 5% darker, you’d do it. You wouldn’t even notice the 5% reduction in light. But here’s the rub. If you’d do it once, you’d do it again and again. Pretty soon you’ll end up rich but living in the dark.

Worse, you won’t even know what went wrong. You’ll try in vain to isolate which 5% decrease did you in, and you’ll conclude that every step of the way seemed like a good one. Each time you got a lot of money for a difference you couldn’t even notice.

This dilemma is especially pronounced when big organizations get involved. Most of us can’t earn a million dollars by making changes to the lighting, but hotel chains can, and they do, which is why hotel rooms are so dark. Of course, it’s not just lighting. That same chain makes the soap bars just a little smaller, and gathers up the tiny profit from each bar of soap for a huge increase in the bottom line. Airlines put the seats in their planes just a little closer together to augment revenue. Oil companies raise the price of fuel by just a cent or two every so often. Call-center managers reduce staff just a tad. Supermarkets provide slightly fewer cashiers. Managers demand just five more minutes out of each employee’s workweek.

And it’s not just the corporate world. Municipalities suffer the same kind of fate when they cut the number of police just a bit. So do school districts that reduce each teacher’s training only a little. And at the federal level, a decision is made from time to time to spend just 1% less on some important program.

What we end up with, though, is schools that don’t work, planes that only young children fit comfortably in, hotels that are too dark to see if your clothes match, phone menus from hell, long lines to buy food, burdensome workweeks, and so forth.

The problem comes from the seemingly desirable goal of maximizing profits combined with the human tendency not to notice small changes.

The only solution I can think of is to agree that maximizing profits is a bad idea in the long run.

To look at another example, imagine a swimming pool. With so much water, it’s hard to imagine that giving away a single cup could make any difference. Yet a pool can be emptied one cup at a time. If you think you can sell one cup and not impact the pool, you’ll end up with lots of money and nowhere to swim.

At first glance, it might seem as though the same mechanism that prevents us from noticing slightly darker rooms also means that a huge hotel chain won’t care about slightly higher earnings. For example, Marriott International had gross revenue of over 12 billion dollars in 2011. That’s over 12,000 million dollars. Does it really matter if it’s 12,321 million or 12,322? Sometimes, maybe not, though other things being equal any CEO or board member will opt for more money instead of less, no matter how small the difference. But other times, even a tiny amount can make a huge difference: if saving just a thousand dollars means not going over budget, even a huge hotel chain might need that $1,000. Or if a bonus for some employee is tied to meeting a certain goal, that $1,000 might be the final step toward getting the bonus.

The overhead cost of making any change might also seem important. Even if smaller bars of soap are cheaper, for example, the one or two cents saved on each bar is offset by the costs of putting someone in charge, of changing the specs, etc. But even though this may mitigate the tendency for our lives to get worse, it doesn’t eliminate it. Furthermore, as companies grow larger, the overhead costs become less significant compared to the potential savings.

Similarly, eventually the soap will be so small, the lighting so dark, the teachers so poorly trained, that a 5% reduction doesn’t net much profit. For example, if a bar of soap weighs 3.5 ounces, cutting 5% means not having to pay for 1/6 of an ounce of soap. Multiplied by over half a million Marriott rooms and 365 days/year (potentially over 180 million guests, but probably closer to 100 million), that’s up to almost 1,000 tons of soap each year saved by that 5% cut. But once the bar is whittled down to only 1 ounce, the same 5% cut saves less than 200 tons. It might not be worth it. Unfortunately, this pattern just means that there might be a lower limit to how bad things can get. Even more unfortunately, as companies grow larger, this limit goes down.

So, again, the only solution I can think of is to agree that maximizing profits is a bad idea in the long run.

Homosexuality, Hypocrisy, and the Bible

About a year ago I chastized Pastor Joel Osteen and others for what I called “hiding behind Scripture.” In particular, Pastor Osteen had just told CNN’s Piers Morgan that he was locked into his anti-homosexual position by the Bible. He is not, and, I believe, he knows it.

Pastor Osteen just confirmed to Oprah Winfrey that he believes that “homosexuality is shown as a sin in the Scripture,” noting that he encourages people to be “willing to change and grow.”

Pastor Osteen just confirmed to Oprah Winfrey that he believes that “homosexuality is shown as a sin in the Scripture,” noting that he encourages people to be “willing to change and grow.”

On the other hand, when Piers Morgan asked him in October whether he supports the Biblical position of a life for a life, Pastor Osteen admitted (in this video): “I don’t know,” because the death penalty is a “complicated issue.”

In other words, Pastor Osteen doesn’t feel compelled to support everything in Scripture. He openly ignores Exodus 21:24, Leviticus 24:20, and Dueteronomy 19:21. He reserves the right — as we all do — to pick and choose.

This is why I don’t think there’s any merit or integrity to his argument that he is forced to condemn homosexuality because Scripture calls it a sin.

As it happens, I don’t believe that Scripture says that, but I do support Pastor Osteen’s right to interpret Scripture as he chooses.

What I don’t support is the way he presents his opinions as unbiased fact.

As far as I’m concerned, until Pastor Osteen takes responsibility for his own words, he’s no better than any other coward who hides from the people he attacks.

Content, Connection, and Compassion: Three Steps to a Productive Religious School

At a National Jewish Book Award ceremony not so long ago, an award recipient took the stage, smiled broadly, and told the audience that “it’s nice to get a prize.” Then she added, “the last time I got a prize was in Religious School…” — for what? — “…for being quiet.”

Yes, she was awarded a prize for simply being quiet, the bar in her school sadly having been set so low that by doing nothing she was already outperforming her peers. (Rabbi Larry Milder expresses a similar sentiment in his song about his experience teaching Religious School: There’s a Riot Going On in Classroom Number Nine.) Equally unfortunately, most of the audience at the award ceremony chuckled in solidarity, probably remembering their own not-so-different experiences in Religious School. Some of them may even have thought, “so you’re the goodie-goodie who got us all in trouble when we were pasting our yarmulkes to the wall.”

Yes, she was awarded a prize for simply being quiet, the bar in her school sadly having been set so low that by doing nothing she was already outperforming her peers. (Rabbi Larry Milder expresses a similar sentiment in his song about his experience teaching Religious School: There’s a Riot Going On in Classroom Number Nine.) Equally unfortunately, most of the audience at the award ceremony chuckled in solidarity, probably remembering their own not-so-different experiences in Religious School. Some of them may even have thought, “so you’re the goodie-goodie who got us all in trouble when we were pasting our yarmulkes to the wall.”

How did this happen, and what can we do about it?

Many Religious Schools seem like case studies in institutional bipolar disorder: children must attend but nothing should be required of them; or everything should be required of them and there should be no consequences for not fulfilling the requirements; or the consequences should be so severe that everyone hates being there; or loving Religious School is so important that the school is turned into a playground where nothing is taught; and so forth.

Hidden in this list of institutionality-disorder symptoms are three of the elements that I believe are crucial to a productive Religious School: content, connection, and compassion.

I think we have an absolute obligation not to waste the time of the students who show up to Religious School. After all, they aren’t allowed to leave. If I go to a lecture and I’m bored, I can walk out. But we don’t give children at Religious School (or public school, for that matter) this prerogative, so I think we have to make sure that their time in class is well spent by giving them challenging and engaging content.

Having fun also seems like a good idea. And some people believe that the best way to have fun is to turn learning time into game time. But I disagree, because, fortunately, children naturally love learning. So I think that by providing a stimulating environment we will also create a place where children enjoy themselves. Schools that dumb down their curriculum to make the place more enticing have it backwards.

Having fun also contributes to my second element of Religious School: connection. If the only point of the school were to convey information, we could distribute textbooks, offer a yearly exam, and do away with the weekly gatherings. But Judaism is not merely a collection of facts to be learned. It is also a sense of connection — to our history, to each other, to the Jewish people, to Israel, and to the synagogue.

Thirdly, I think our school has to offer compassion to people — children and parents — whose lives are increasingly lacking that vital component. Too many parts of our lives are uncompromising and rigid, forcing us to adapt to them rather than letting us be ourselves. Our school can offer an island of relief against this troubling trend.

Taken in isolation, any of these three aspects — content, connection, and compassion — can lead us astray. If we focus only on content, our Religious School will lose its soul. Connection by itself won’t work, because we have to offer something to be connected to. And compassion alone threatens to make the school irrelevant to people who are already thriving.

But in combination, I think these three goals can help provide the foundation of a school worthy of the collective energy we all invest in it.

[Reposted from the Vassar Temple Blog, in turn reprinted from my article in the Vassar Temple January, 2012 bulletin.]

Fixing Half the Problem

It’s easy to fix half a problem if you don’t mind making the other half worse.

And I think this is what we see with President Obama’s plan to help home owners refinance at a lower interest rate.

And I think this is what we see with President Obama’s plan to help home owners refinance at a lower interest rate.

At first glance, it seems like a good idea, because home owners will save money thanks to lower mortgage payments. But that’s only half the story.

The other half is that people who have invested in real estate will earn less.

For example, on each $100,000 of mortgage loans, an interest-rate drop from 6% to 4% saves a home owner almost $1,500 per year. If, let’s say, one million people shave two percentage points off an average of $250,000 in mortgages, then one million people will save on average upwards of $36,000 each over the next ten years.

But by exactly the same token, investors in real estate — banks, but also pension funds and the like — will collectively lose more than $36 billion over the text ten years.

Just by way of example, one adverse reaction will be to the New York State Teachers’ Retirement System, which has some $1.34 billion invested in real estate. If the return on that $1.34 billion drops from from 6% to 4%, the fund will earn $27 million a year less, for a total loss of $270 million over ten years.

In short, there’s no free lunch here. When some people save money, other people earn less from their investments.

Like a ship taking on water, America is sinking from debt. And like two groups of sailors — each trying to save half the boat by shifting the water to the other side — our leaders seem focused on solving half the problem even if they make the other half worse.