Archive

Reflections on Hurricane Sandy

Astonishingly, that was the calm before the storm, though I didn’t know it at the time.

As night fell, the winds really picked up, roaring louder than any bit of nature I’ve ever heard, save perhaps thunder. A local radio station — my only link to anything beyond the walls around me — reported gusts of over 100 miles per hour: the very air I breathe was racing faster than I’ve ever driven.

Living essentially in the forest, I’ve spent many dark nights unable to communicate with the outside world. I’m prepared for power outages.

But I wasn’t prepared for this.

I wasn’t actually afraid for my own safety (though perhaps I should have been), but my pulse was racing and my heart pounding nonetheless. But for the cacophony outside, I’m sure I would actually have heard it.

In retrospect, I was reliving part of my past.

I re-experienced what my ancestors knew: Nature is awesome, not only in the modern “isn’t it amazing” and “I must take a picture” sense, but more along the lines of the transcendent “my greatest accomplishments pale in comparison,” and “I am both terrified of this and irresistibly drawn to see it.”

All in all, I was lucky. Dozens of people died, but I wasn’t harmed. A tree fell on my neighbor’s house, but mine is fine. (Other neighbors saw a tree fall on their backyard trampoline, voicing the opinion that it should have bounced.) Some not-too-distant communities were swept away, but I was unaffected by flooding.

Sandy left me with no water, heat, phones, electricity, cell reception, or Internet service, putting me in the category of the lucky ones.

Sanctity Doesn’t Have to be Solemn

This is our “holiday season”: Rosh Hashanah (at least one day, two for many), then Yom Kippur (never more than one day), Sukkot (about a week), and finally Simchat Torah and Shmini Atzeret.

It’s these last two that cause confusion.Simchat Torah, literally, “The Joy of Torah,” is either the 8th day of the seven-day holiday of Sukkot (if you keep only one day of Rosh Hashanah) or the 9th day of the eight-day holiday of Sukkot (if you keep two).

Shmini Atzeret, literally, “the eighth, a convocation,” is always the 8th day of Sukkot, whether or not Sukkot has eight days or only seven. (It also gives us the chance to use the word “convocation,” which doesn’t otherwise pop up too frequently.)

Generally the first and last days of a holiday are “yontiv,” days on which, more or less like Shabbat, we rest from work. So the first and last days of the seven-day holiday of Passover are both yontiv, or, if you keep eight days, the first two days and the last two days. Similarly, the first day of the seven-day holiday of Sukkot — or the first two days of the eight-day holiday of Sukkot — are yontiv, along with the last day or so.

Generally the first and last days of a holiday are “yontiv,” days on which, more or less like Shabbat, we rest from work. So the first and last days of the seven-day holiday of Passover are both yontiv, or, if you keep eight days, the first two days and the last two days. Similarly, the first day of the seven-day holiday of Sukkot — or the first two days of the eight-day holiday of Sukkot — are yontiv, along with the last day or so.

This background is important for understanding a discussion in the Talmud, that ancient compendium of Jewish law that examines and directs Jewish practice. For example it’s the Talmud that tells us when and how to light Hanukkah candles (put them in the menorah from right to left, light them left to right), how often to pray (thrice daily, unless you don’t feel like it), when one bird is similar enough to a kosher bird that it, too, counts as kosher (if they naturally interbreed or if their eggs are indistinguishable), which activities detract from rest on Shabbat and yontiv (travel, for instance), and, of course much more.

So it should come as no surprise that the Talmud gives us regulations regarding the Sukkah: It must have four, three, or two and half walls; must offer a view of the stars; must have more shade than sun; must be at least ten hand-breadths high, but less than about 10 yards; and so on.

Then the question arises (on page 23a of the section called “Sukkot,” if you want to follow along at home) of whether a Sukkah can be built on top of a camel. And the answer is, no, because the Sukkah is meant for the entire seven- or eight-day period of Sukkot, but sitting on a camel counts as travel, which, as we just saw, detracts from yontiv. So a Sukkah on a camel would be useless for at least two of the seven days of Sukkot (or four of the eight).

The next question is whether an elephant can be used for one of the walls of the Sukkah. And, again, the answer is no, because it might run away, invalidating the Sukkah. What about a dead elephant? Sure! As long as the elephant is as least ten hand-breadths in height, we’re good to go. Smaller animals, of course, might be ten hand-breadths in height only when standing but not when lying down. These, according to the Talmud, should therefore be suspended by ropes from above. (Please don’t try this at home.)

Now, Rabbis Meir, Yehudah, and Zeira, along with the other participants of this Talmudic debate, knew full well that hanging an animal just so it couldn’t lie down was a violation of the prohibition against cruelty to animals, and other obvious considerations prevent beasts of burden from doing double duty as structural supports.

So what are we to make of all of this? To me, the most important lesson is to try to enjoy whatever we do. We don’t have to be somber to take something seriously, and sanctity doesn’t have to be solemn. Torah is joyous.

And we have a holiday just to remind us. Happy Simchat Torah.

Truth, Lies, and Sins

I’ve been thinking a lot about truth lately.

I’ve been thinking a lot about truth lately.

For one thing, it’s been in the national news, for instance when Neil Newhouse, a senior advisor to presidential candidate Mitt Romney, told ABC news that, “We’re not going to let our campaign be dictated by fact-checkers.” That sounds a lot like a dismissal of the truth. Could that be because lying isn’t illegal?

I suspect that it would be a career-ender, or worse, for a campaigner to suggest that “we’re not going to let our campaign be dictated by judges,” or in any other way to suggest that following the law wasn’t supremely important. But, apparently, it’s okay to dismiss the truth.

This callousness about the truth — and the widespread willingness to accept compromises on the truth — is especially surprising in a culture marked by such catchphrases as “truth, justice, and the American way” (originally from Superman) and “the truth shall set you free” (from the New Testament book of John), and whose founding father is lauded because he could not tell a lie.

Truth has a distinguished history: Aristotle loved both Plato and truth, but demands the truth be put first (amfoin gar ontoin filoin osion protiman tin alitheian — “Nicomachaen Ethics” i.6.1), Cato promotes speaking truth even though it’s hard (vera libens dicas, quamquam sint aspera dictu — “Dicta Catonis”), and Cicero claims that seeking the truth is particularly human (hominis est propria veri inquisitio — “De Officiis” i.4.13). Confucius, too, is in favor of truth, arguing that those who hear the truth in the morning can die without regret in the evening (Analects vi.18). So why have we changed our attitude?

Again, is the problem that lying is legal?

I bring up legality because for some time I’ve been interested in the interplay between the law and ethics, and, in particular, the lack of a codified morality in America and other Western nations. People are allowed, even encouraged, to do anything legal, while it’s often okay to do something illegal if you don’t mind the penalty. (For example, I’m told that UPS truck drivers in New York City are told to park wherever they want, because the fines cost less than late deliveries.) Most modern Western citizens are so used to this mentality that they find it hard to imagine things being any other way.

But there are other approaches.

TEDx: Bible Translation and the Next Generation

The Ten Commandments are interesting in that they single out some laws as having moral content. Their point is that killing, for example, is a matter of both legality and morality. (I have more in this TEDx presentation.)

And all of this brings up an essay I wrote for We Have Sinned: Sin and Confession in Judaism, which was just released last week. Central themes of that book include the nature of sin, its role in our lives, and the modern relevance of some ancient prayers that list our sins — both those we have committed and numerous ones we haven’t.

My focus there (in addition to serving as chief translator) is what we learn from being bombarded by sins:

Once we accept that some things are wrong, we have to examine our behavior, even our legal behavior, more closely:The first [thing we learn from the Al Chet prayer about sins] is that some things are wrong. This basic Jewish tenet, so obvious to those who already know it, is neither intuitive nor universal. There are young children who take what they want only because they want it, never asking the deeper, Jewish question of Al Chet: “Is it right to do this?” For them, the world is divided not into right and wrong but, rather, simply into “what I want” and “what I don’t want.”

Most of us, after all, aren’t murderers. Our lives are more subtle. Deception is an accepted part of negotiation, but is there a point at which we might go too far? Can I lie to the police to avoid getting a traffic ticket? Violence is part of a successful defense of peace. Is it justified? Doling out punishment to children helps them navigate the world as adults. How strict should I be? Misleading the ones we love can be an invaluable gift. What do I tell the people I love? Again and again, we wonder: have we done the right thing?

My general point is that taking time to focus seriously on sin is more important now than ever, if for no other reason than we have to remember that some things — like lying, I suspect — are legal but still wrong.

For that matter, Thoreau wrote that “it takes two to speak the truth — one to speak, and another to hear.” Are we who put up with untruths as guilty as those who speak them?

What do you think? Is lying to get elected okay? Is deception as part of negotiation? Where do you draw the line? And how do you know?

Two Monologues And No Dialogue: How (Not) To Talk About Religion and Social Issues

The past few days have highlighted for me once again the degree to which our religious nation is divided.

The past few days have highlighted for me once again the degree to which our religious nation is divided.

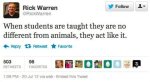

The first example comes from the hugely popular megachurch pastor Rick Warren and his recent reaction when a man slaughtered moviegoers in Aurora, CO. Pastor Warren blamed the violence on those who teach evolution. “When students are taught they are no different from animals, they act like it,” he wrote on his Twitter and Facebook accounts. (He has since deleted his tweet, but not before on-line media such as The Examiner wrote about it.)

The first example comes from the hugely popular megachurch pastor Rick Warren and his recent reaction when a man slaughtered moviegoers in Aurora, CO. Pastor Warren blamed the violence on those who teach evolution. “When students are taught they are no different from animals, they act like it,” he wrote on his Twitter and Facebook accounts. (He has since deleted his tweet, but not before on-line media such as The Examiner wrote about it.)

The second example comes from The Gospel Coalition’s collection of blogs, which featured a post by author and pastor Jared Wilson. In it, Pastor Wilson explains that God’s natural order of things is for men to dominate women, and that rape results from men and women who try to fight that God-ordained hierarchy. (Like Pastor Warren, Pastor Wilson removed the blog post, under protest. Excerpts and an analysis can be found here: “Complementarians and Martial [sic] Sex: The Jared Wilson / Gospel Coalition Saga.”)

The same Gospel Coalition is promoting an anti-homosexual marriage blog post: Gay Is Not the New Black, written by Pastor Voddie Baucham.

The same Gospel Coalition is promoting an anti-homosexual marriage blog post: Gay Is Not the New Black, written by Pastor Voddie Baucham.

Most of the reactions to these kinds of claims come in one of two varieties: (1) How could anyone possibly agree? or (2) how could anyone possibly disagree?

The naysayers cite their evidence: Pastor Warren has misunderstood the allegorical nature of Genesis, and misunderstood the natural world in that animals don’t tend to slaughter their own kind. Pastor Wilson has ignored passages such as 1 Corinthians 7:3-5 that put men and women on a par in the marriage bed. Pastor Baucham has taken 1 Corinthians 6 out of context while ignoring other relevant passages of Scripture. And so forth.

Then the claimants respond with their own evidence: Morality comes from religion, Colossians 3:18 subordinates women to men, and Leviticus forbids homosexuality.

As a Bible scholar, it’s abundantly obvious to me that both sides find ample support in Scripture. The Bible doesn’t take a clear stance on evolution, why people commit violence, or what marriage looks like — not beyond what we all agree on, at least.

But I don’t think that these are debates about evidence, science, or religion. In fact, I don’t think they are debates at all. They are, rather, collections of diatribes — monologues, as it were, instead of dialogues. And that’s because we tend to focus on our self-selected evidence instead of our motivations.

For example, if Pastors Warren, Wilson, and Baucham discovered that they were wrong about the intent of the Bible (as I believe they often are), would they change their minds? If a new manuscript surfaced, or a better understanding of the text presented itself, would they care? My suspicion is they would not.

Like slavery in its day and usury before that, these issues don’t start with the Bible. They start with how we feel.

So if we’re going to have a real conversation, I think it has to be about our motives, not the texts we choose to support them.

Content, Connection, and Compassion: Three Steps to a Productive Religious School

At a National Jewish Book Award ceremony not so long ago, an award recipient took the stage, smiled broadly, and told the audience that “it’s nice to get a prize.” Then she added, “the last time I got a prize was in Religious School…” — for what? — “…for being quiet.”

Yes, she was awarded a prize for simply being quiet, the bar in her school sadly having been set so low that by doing nothing she was already outperforming her peers. (Rabbi Larry Milder expresses a similar sentiment in his song about his experience teaching Religious School: There’s a Riot Going On in Classroom Number Nine.) Equally unfortunately, most of the audience at the award ceremony chuckled in solidarity, probably remembering their own not-so-different experiences in Religious School. Some of them may even have thought, “so you’re the goodie-goodie who got us all in trouble when we were pasting our yarmulkes to the wall.”

Yes, she was awarded a prize for simply being quiet, the bar in her school sadly having been set so low that by doing nothing she was already outperforming her peers. (Rabbi Larry Milder expresses a similar sentiment in his song about his experience teaching Religious School: There’s a Riot Going On in Classroom Number Nine.) Equally unfortunately, most of the audience at the award ceremony chuckled in solidarity, probably remembering their own not-so-different experiences in Religious School. Some of them may even have thought, “so you’re the goodie-goodie who got us all in trouble when we were pasting our yarmulkes to the wall.”

How did this happen, and what can we do about it?

Many Religious Schools seem like case studies in institutional bipolar disorder: children must attend but nothing should be required of them; or everything should be required of them and there should be no consequences for not fulfilling the requirements; or the consequences should be so severe that everyone hates being there; or loving Religious School is so important that the school is turned into a playground where nothing is taught; and so forth.

Hidden in this list of institutionality-disorder symptoms are three of the elements that I believe are crucial to a productive Religious School: content, connection, and compassion.

I think we have an absolute obligation not to waste the time of the students who show up to Religious School. After all, they aren’t allowed to leave. If I go to a lecture and I’m bored, I can walk out. But we don’t give children at Religious School (or public school, for that matter) this prerogative, so I think we have to make sure that their time in class is well spent by giving them challenging and engaging content.

Having fun also seems like a good idea. And some people believe that the best way to have fun is to turn learning time into game time. But I disagree, because, fortunately, children naturally love learning. So I think that by providing a stimulating environment we will also create a place where children enjoy themselves. Schools that dumb down their curriculum to make the place more enticing have it backwards.

Having fun also contributes to my second element of Religious School: connection. If the only point of the school were to convey information, we could distribute textbooks, offer a yearly exam, and do away with the weekly gatherings. But Judaism is not merely a collection of facts to be learned. It is also a sense of connection — to our history, to each other, to the Jewish people, to Israel, and to the synagogue.

Thirdly, I think our school has to offer compassion to people — children and parents — whose lives are increasingly lacking that vital component. Too many parts of our lives are uncompromising and rigid, forcing us to adapt to them rather than letting us be ourselves. Our school can offer an island of relief against this troubling trend.

Taken in isolation, any of these three aspects — content, connection, and compassion — can lead us astray. If we focus only on content, our Religious School will lose its soul. Connection by itself won’t work, because we have to offer something to be connected to. And compassion alone threatens to make the school irrelevant to people who are already thriving.

But in combination, I think these three goals can help provide the foundation of a school worthy of the collective energy we all invest in it.

[Reposted from the Vassar Temple Blog, in turn reprinted from my article in the Vassar Temple January, 2012 bulletin.]

The Subtext of Our Lives: Unetaneh Tokef and the High Holidays

“Who shall die by fire, and who by water?”

For many people, that question — part of the haunting Unetaneh Tokef prayer — is reason enough to boycott the Days of Awe. After all, the text of that famous medieval poem offers a simple, clear answer to why people suffer: it’s their own fault. They were given a perfectly fair trial (conveniently featuring God as prosecutor, defense attorney, witness, and judge), and every last chance to return to the right path, but they stubbornly refused God’s lifeline. So they died.

But the subtext of Unetaneh Tokef tells a different story, referencing the Book of Job more than any other. For example, the “still small voice” of the Unetaneh Tokef text mirrors Job 4:16. The text of the next line of Unetaneh Tokef deals with angels, as does Job 4:18. Literally reading between the lines, we find Job 4:17: “Can humans be acquitted by God?”

The text and subtext vehemently disagree, so what looks like an answer — people die because God makes them — is really a question: What’s going on here?

The High Holidays in general are like that, and so too are our lives. We have a text. But we need the subtext to understand it. And the simple, clear answers are usually wrong.

[Adapted from my essay “How was Your Flight” in Who by Fire, Who by Water: Un’taneh Tokef, pub. 2010 by Jewish Lights Publishing, ed. Rabbi Larry Hoffman.]

Accidental Mutineers

With Rosh Hashanah less than a week away, our thoughts turn to starting a new year, and, we hope, improving on the old one. The theme of asking for forgiveness is a common one. But we pay less attention to the other side of the same coin: have we created an environment that lets others apologize to us?

We usually find it easier to see the faults in those around us than to recognize our own. The shortcomings of family members, coworkers, and friends leap out at us in vivid detail, while our own imperfections remain obscured behind veils of psychological obfuscation.

So what do we do when we see that a parent is needy or a boss insecure, a spouse jealous or a friend unsupportive, a child ungrateful or an employee combative?

Like all instruments of power, our knowledge of other people’s faults — so clear to us and yet invisible to them — can be a force for betterment or for destruction.

In this regard, the 1954 film The Caine Mutiny is a brilliant study of how we deal with what’s wrong with other people.

Captain Queeg, in command of the U.S.S. Caine, is a well-meaning and capable commander, but years of combat have taken their toll and he is also nervous, obsessive, and prone to paranoia. As is frequently the case, those around him see his faults right away, while he himself remains practically unaware of them.

What, then, do his shipmates do?

Rather than try to work with their captain, rather than accepting his failings and trying to help him overcome them, rather than compensating for what he cannot do, the officers of the ship antagonize Queeg. They scoff him. The provoke him. They follow the letter of his orders even when they know it’s a bad idea.

In this combative and unsupportive environment, Queeg’s insecurities worsen and his paranoia becomes more pronounced. “Sometimes the captain of a ship needs help,” Queeg pleads. But his subordinates use his weakness against him. “Look at the man. He’s a Freudian delight,” one officer tells another, hoping to make a case that the captain is unbalanced.

Eventually the ship finds itself maneuvering around a typhoon. The crew no longer trusts their isolated captain, and they relieve him of command.

The key to the movie is the trial for mutiny. The crew are found not-guilty, because by the time the typhoon hit, Captain Queeg was unable to make sound decisions. But they are also found morally culpable, because they paved the way to the captain’s demise, in the process almost destroying the boat and ending their own lives.

What will we do next year when we see the shortcomings in those around us?

Like the officers on the Caine, we have a choice. We can try to create a tolerant, forgiving environment. Or we can use other human beings’ flaws to our own short-term advantage and amusement.

Will we choose well?

Or we will become accidental mutineers?

All I Ask

The Jewish month of Elul is traditionally connected to Psalm 27. And with its familiar haunting melody, the 4th verse of the Psalm is particularly well known: “I ask only one thing of God — it is what I want: To live in God’s house all the days of my life, to gaze upon God’s glory, and to visit God’s Temple.”

The nuances of the words — is it “glory” or “beauty,” “visit” or “seek,” etc. — are less interesting to me than the obvious contradiction in the line, because after specifically claiming only to want “one thing,” the Psalmist lists three: The Psalmist wants (1) to live in God’s house, (2) to gaze upon God’s glory, and (3) to visit God’s Temple.

What are we to make of this? Why can’t the Psalmist count to one?

I see insight into the nature of being human and wanting.

The Psalmist wants to live in God’s house not just for the sake of being there, but for what it will lead to, namely, seeing God’s glory. The next lines, verse 5-6, continue in a similar vein: …because in times of trouble God will hide me and keep me safe, bring me safely out of reach, and bring me victory over my enemies who are all around me. The Psalmist has the whole thing planned out. If he can only manage to live in God’s house, he’ll see God’s glory, then get God’s defensive protection, which will naturally lead to an offensive victory over his adversaries. “If only I could live in God’s house,” the Psalmist thinks, “I could finally beat them!”

The Psalmist has perpetrated his own internal bait-and-switch on himself, confusing what he wants with how he will get there. The result is a jumble in his mind, with tranquility, Godliness, safety, and retribution all mixed up.

It seems to be human nature to confuse our desires with the paths that might lead to them, and advertisers exploit this trait of ours.

Coca Cola’s website, for example, displays a prominent image of a Coca Cola bottle with the caption “open happiness.” Who wouldn’t like a little more happiness? The advertising at Coca Cola nudges us into thinking that Coke will lead us in that direction. Next thing we know, we get confused between buying Coke and becoming happier.

Most of the material goods we think we want work the same way. We get confused and think that they are a path to happiness. Then when we buy something and it doesn’t make us happy, we come to the reasonable but wrong conclusion that we have bought the wrong thing. Like Charlie Brown — who is the only one who doesn’t know that Lucy will never cooperate — we think that all we have to do is try again and buy something else. Most of us keep stumbling, and we never learn that what we really have to do is play a different game.

Non-material desires are really no different. We want power, a loyal following, recognition, or what-not, but for what we imagine they will lead to, not for what they are.

I have nothing against money or material possessions. (As the Russians say, it’s better to be healthy and rich than sick and poor.) Money can buy really important things like medicine and education and food, and make it easier to visit friends and fix the world, just to name a few benefits. On a smaller scale, if buying new clothes makes you happy for a day, it seems like money well spent.

We just have to be careful not to get confused. The Psalmist’s mistake is not that he wants to be with God or that he wants to defeat his enemies. His error is right at the start of verse 4: “I ask only one thing.”

We are seldom seeing clearly when we think that our lives lack only one thing or that with the addition of one thing our lives would be perfect. Yet even without the incessant prodding of advertisers, it would be part of our very nature to make this mistake. Ignore it, and we can’t even notice when “one” is “three.”

But once we see past it — once we differentiate between what we want and what we think it will do for us — we begin our journey toward spending our time, money, and energy wisely.

Paving and Paradise

By Joel M. Hoffman

Pave over a field and an amazing thing happens each spring: grass grows through the blacktop. Somehow, even the industrial strength of the pavement, powerful enough to support the tonnage of trucks, can’t stop a single, fragile, nascent blade of grass yearning for light.

At this time of year, we are like the grass.

Our springtime holiday of freedom ended a short while ago. Our next major celebration comes exactly fifty days after Passover, on May 29, this year. It’s Shavu’ot, the day that commemorates when we stood at Mt. Sinai and received the Torah. The 49-day period in between is called the Omer, and it’s a time of spiritual limbo. We have our freedom, but we don’t yet have guidance from Torah. So we can do what we want, but we don’t know what we should do. The Omer is our yearly moral navigation check-up, a time to ask: “Am I going in the right direction?”

The seven week period of the Omer (“seven weeks of seven days,” it’s called in the Torah) has become so important that we traditionally count each day. When we do, we note the total number of days, and also how many weeks they comprise. Mother’s Day, for example, falls this year on the 31st day of the Omer, which is four weeks and three days into the Omer. That’s how it’s done.

It’s a period of high emotion. For some people, most of the Omer is a season of mourning, during which weddings are forbidden and even pleasurable music is not allowed. But the 33rd day of the Omer — lag ba’omer, in Hebrew — is a day of rejoicing. So is Jerusalem Day, on the 43 day of the Omer. (If you want a traditional springtime wedding, it has to be on the 33rd day of the Omer, making that day one of the hardest times to find a wedding hall in Israel.)

We juxtapose confirmation with Shavu’ot, using our celebration of Torah to publicly acknowledge the students who have chosen to continue their Jewish education. Bar/bat mitzvah may have been when they became Jewish adults, allowed to make their own ritual decisions, but without Torah, how will they decide what to do? That’s one reason we hope they continue to study.

Shavu’ot usually comes around the last day of Religious School, as if to underscore the connection between going to Religious School and working to accept Torah. On Shavu’ot, we celebrate another successful year of school.

And Shavu’ot, like Memorial Day, marks the beginning of summer.

In Aramaic — the language of the Talmud and of prayers such as the Kadish — the word for Torah is oraita, literally, “the light.” In this context, we are all like the grass that breaks through the blacktop. The grass is searching for the sun. We are searching for our light, the light that is Torah. And our job during the Omer is to find it. Like for the grass, sometimes seemingly insurmountable obstacles block our path. Instead of blacktop, we have to overcome petty rivalry, jealousy, hatred, and ego, just to name a few. These are often harder than pavement.

There’s another way our journey is more difficult than that of the grass. Gravity causes chemicals called auxins to pool in the lower part of the grass shoot, which then has no choice but to grow upward. It will eventually find light. We have more freedom. We can go anywhere we want, do anything we please. We can grow toward Torah, or shift away from it. The Omer is our time to ask if we are going in the right direction: Are we becoming better people? Are we working toward the right goals? Are we proud of where we’re going and what we’re working to do?

We have one final thing in common with the grass. We can’t see the light until we overcome the obstacles blocking our path. The Omer can be dark and frustrating, but if we spend our time wisely, it will be worth it.

Do Not Oppress The Stranger

By Joel M. Hoffman

“Do not oppress the stranger,” the Bible warns us over and over again, “for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.” The saga of the Jewish people is to know what it’s like not to fit in, which is why this notion of welcoming the stranger defines Judaism as much as any other central precept.

The English word “stranger” offers us additional insight into what the Bible is talking about, because our word is nicely ambiguous. A “stranger” is someone from another place, but, equally, “stranger” is “more than just strange.” And of course that’s why being from another place is so hard. When you go somewhere new, you think everyone else is strange, and they all think you are. Visitors wonder at our customs just as we wonder at theirs.

So we learn not only that we shouldn’t oppress the stranger, but equally that we shouldn’t oppress people who are strange.

It’s important, for being from a foreign place is only one way of being strange. There are many others. In fact, Scott Dunn teaches that anyone who lives honestly in the world is perceived as a little bit strange. People wear odd clothes, walk crooked, have funny body shapes, listen to bizarre music, say strange things, have silly habits, and on and on. Are we careful not to oppress them?

I know a student with what she calls — having been told to call it so by her doctor — ADD. I understand the ‘A.’ It stands for “attention.” I even understand the first ‘D,’ which stands for “deficit.” She has an attention deficit, which is a not-so-polite way of saying she has trouble paying attention to one thing at a time. A nicer way to explain her situation would be that she can focus on more than one thing at a time, a skill that helps her notice connections that others often miss, and a quality that makes her a consistently interesting interlocutor.

As bad as the first ‘D’ is, though, it’s the second that really troubles me. It stands for “disorder.” What happened to “do not oppress”? When we classify people’s thinking — their natural way of being in the world — as a “disorder,” haven’t we pretty much destroyed any hope of welcoming them?

To be sure, some behaviors and conditions are more conducive to happiness and success than others. Just as I wear eye glasses so I can see better, attention deficit should be dealt with (if possible) when it stands in the way of a person’s goals. By the same reasoning, life-threatening obesity should be managed. And obsessive-compulsive behavior — normally called obsessive-compulsive disorder, once again making it hard to welcome those with the condition — can be a curious quirk or a debilitating disease, and in the latter case treatment seems like a good idea.

But whatever the nature of the oddity, Judaism expressly forbids negative name calling. We are all strange in our own way, and words like “disorder” have no place in our holy community. We can recognize our differences — and even note that some differences are advantageous or disadvantageous — without stacking people up in a hierarchy of normalcy.

This message is a cornerstone of our school. “No one fails Judaism,” Rabbi Manny Gold teaches, “but if we’re not careful, Judaism can fail them.” Part of my job as Director of Education is to make sure that our school welcomes whoever walks through our doors, even though some students will seem strange. After all, we’re all strange. Some of us just hide it better than others.

Purim arrives this month. It’s a holiday that freely mixes silly masquerading with serious messages. It’s also a time when we all practice being strange and, if we’re really doing things right, practice welcoming those who are strange.

“Do not oppress the stranger,” we are taught. This year, let’s use our Purim partying and seemingly frivolous merrymaking as a mental reminder not to oppress the stranger, the strangest, or even the merely strange.